We're all too used to exploiting web applications to hijack someone else's website and post our own stuff, but did you know that there's a much easier way to take over a site? To discuss the much overlooked topic of DNS security, first we have to go over the basics of how the DNS functions and what DNS records are.

# How the DNS works

Imagine you're trying to send a box of fruits to your client Mr. Cole as a new year's gift. The problem is, you don't have his address. You can't just write 'Mr. Cole from the Finance Department of the Orange Company' on the packaging because the postman has no idea who Mr. Cole is,let alone where he lives. What do you do?

You could possibly google the phone number of the Orange Company and try to reach the Finance Department through the receptionist. Then perhaps the intermediate contact would be able to put you through to Mr. Cole himself, or better yet, look up Mr. Cole's address in their directory and save you the trouble.

What you just did is similar to how the DNS works.

In the digital world, machines are located via IPs (a set of numbers), much like how every house and building is assigned a unique address. But how tedious it would be if you had to memorize the exact address of each of your favorite restaurant? Couldn't you just type 'John's Pizza' and have it pinned on your Google Maps?

This is where domain names come in. A domain name is essentially a human-friendly alias for its numerical counterpart IP, making our lives less painful by providing a easily distinguishable tag. This is great and all, but now we need someone else to do the translation for us.

Back in the days, we had operators checking the yellow pages, but now in modern times, this routine job is delegated to the Domain Name Server (DNS). The DNS is equivalent to a giant directory-checking service, mapping domain names (human-readable google.com) to IP addresses (machine-comprehensible 172.217.160.78) and providing answers to queries from around the globe.

On such a large scope, surely this task cannot be performed efficiently by a single entity. The operator would be overwhelmed with incoming calls before having a chance to even pick up the phonebook. Instead, it would require a hierarchy of operators to accomplish such a feat. For example, we would have city-level operators responsible for keeping the contact information of all the companies in Miami. Then we would also have state-level operators keeping the numbers of the city-level operators, and so on to the region-level and nation-level operators. It's implausible to keep large millions of records in one's yellow pages as it would simply take forever to look up, so each operator will only note the most recently and frequently used records in his book, as well as the highest-level operators. When we query for a lookup, we reach a customer-facing operator, who in turn helps us propagate the request through the hierarchy in search for an answer.

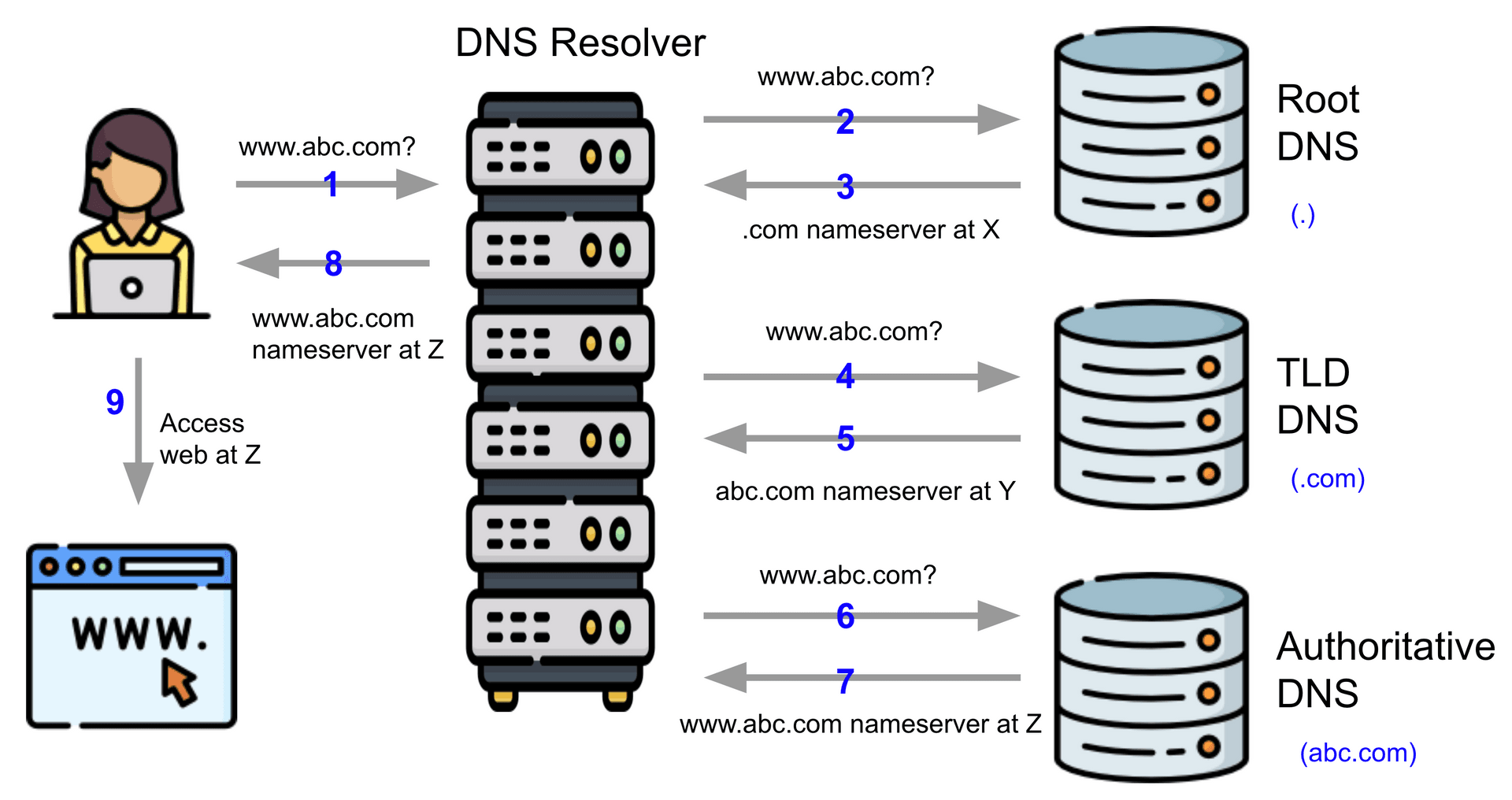

The DNS's tree-structured mechanism can be illustrated with the example below. To clear some terms out of the way, we will refer to the customer-facing operator as the 'DNS resolver', the operators on the hierarchy as 'DNS servers', and the yellow pages as 'caches'.

DNS Lookup

It's black friday, and Ann is ready for a shopping spree. She tries to access www.abc.com, and the following happens in seconds:

- Ann's browser reaches out to a DNS resolver

- The DNS resolver checks its caches for a match. Uh oh,

www.abc.comnot found,abc.comnot found,comnot found. The search fails, so the resolver reaches out to the highest-level DNS: the Root DNS in charge for the.domain. - The Root DNS finds a match for the second-highest-level operator (or the Top Level Domain(TLD) DNS) responsible for

.com, and refers the resolver to the corresponding address. - The resolver queries the

.comTLD DNS forwww.abc.com - The TLD DNS finds a match for the next level operator (or the Authoritative DNS) responsible for

abc.com, and returns the referring information. - The resolver queries the

abc.comAuthoritative DNS forwww.abc.com - The Authoritative DNS does find a hit for

www.abc.comand finally an IP address is returned! - The DNS resolver replies to the browser with the finalized answer, which may be one or more IPs.

- The browser initiates an HTTP (web) request and Ann accesses the site successfully.

Whew, what a laborous journey! As the world's possibly largest distributed database system, the ability to achieve lightning speed queries and seemless synchronization is paramount. So, what shortcuts can we take?

Recall the personal yellow pages each operator kept separately. We called them caches because their main purpose was to cache, or store, the most popular information for frequent access. If someone had already asked for www.abc.com before Ann, the resolver would have already gone through the lengthy process and stored the result in its cache. Subsequently, when receiving queries for www.abc.com, the resolver could simply fetch that record readily in memory and skip steps 3 to 7. Even if the resolver didn't have an answer for www.abc.com, it could start from step 6 if it knew abc.com. Unless the DNS cache has just been purged, a DNS resolver usually already knows the addresses of several TLD DNS and the Root DNS, making full repetition of the steps highly unlikely.

Furthermore, DNS records don't stay in the cache forever, even if it's a service you use daily, like Google. Each record comes with a tag on it: the TTL (Time-to-live) value. As the name implies, this number specifies "how long the record can live in cache" before it becomes "stale" and must be discarded. This "freshness indicator" helps circulate DNS records so that any update of information can be propogated across the internet and DNS servers will always store the latest version. Imagine that you changed the IP address of your site from 101.102.103.104 to 201.202.203.204. If TTL wan't present, resolvers that had 101.102.103.104 in their caches will continue to serve this outdated information to their clients unknowingly. With the TTL parameter, let's say set to 1 hour, we can rest assured that resolvers will have to query for new records within an hour maximum, and our adjustments will fully take effect afterwards, guiding visitors to 201.202.203.204.

Let's recap a bit and summarize the roles:

- Root DNS: Highest-level DNS servers, supervised by ICANN. There 13 logical names and 600-700 physical servers around the world, storing information on TLD DNS. This information is known to all DNS resolvers.

- TLD DNS: Second-highest-level DNS servers, overseen by IANA, a branch of ICANN. Stores information on Authoritative DNS for top-level domains such as

.com,.net,.org,.tw. - Authoritative DNS: Other lower-level DNS servers, and usually the last stop during DNS lookups. Supervised by the owner of the domain.

- DNS Resolver: The client-facing operator who puts you on hold until it resolves an answer. Keeps a cache containing records for the most frequently and recently queried domains to speed up the process.

# DNS Records

Today we'll talk about the most common types of records: SOA, A, AAAA, CNAME, NS, MX, TXT, SRV, PTR.

There are other less common ones, but we'll leave them out for now: DNSKEY, CAA, IPSECKEY, RRSIG, NSEC, AFSDB, APL, CDNSKEY, CERT, DCHID, DNAME, HIP, LOC, NAPTR, P, SSHFP.

# SOA

Before diving into SOA records, we must first introduce the concept of DNS zones. Many people mistake "a domain and its subdomains" as a zone, but in fact, a zone is just a set of domains grouped for easier administration.

Let me illustrate this with an example. Imagine your company abc.com has 3 subdomains blog.abc.com, news.abc.com, internal.abc.com. With heaps of tasks on your plate, naturally you want to perform bulk changes without having to repeat tedious and error-prone work, so you group all the domains in one zone. However, you soon find yourself in an awkward situation, struggling to apply bulk configuration to the zone without negatively affecting individual sites. Though abc.com, blog.abc.com, and news.abc.com are all public facing sites with regular visitors, internal.abc.com is an staff-only internal portal. You wouldn't want the internal site exposed, but you don't want public sites to have too many restrictions either. The conflict in nature and purpose of these domains makes it difficult to execute granular control under shared configurations. This is when you might consider extracting the odd from the bunch and make internal.abc.com an individual zone, so that the portal and future sensitive domains can still be administered together, getting the best of both worlds.

To conclude, a DNS zone can be one domain, multiple domains, or a domain and several subdomains, depending on how you want to group them. A DNS server can also host multiple zones.

Every zone is represented by a zone file which is essentially a text document containing all records under the DNS zone, starting with the record that describes the metadata of the zone: the 'Start of Authority' (SOA) record. There is ususally one DNS responsible for maintaining the zone file, which we refer to as the primary nameserver, and several other secondary nameservers for redundancy and load balancing purposes. The zone file is read-only for secondary nameservers, so they update their copy of the zone file via a process called a zone transfer.

With example.com as an example, the fields in the SOA record and their descriptions are summarized below.

| Field | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| name | example.com | |

| record | SOA | |

| MNAME | ns.icann.org | the primary nameserver in the zone |

| RNAME | noc.dns.icann.org | the administrator's email. The first dot translates to @, so it becomes noc@dns.icann.org |

| SERIAL | 2021110801 | the serial number for the current version. Secondary nameservers are notified when this changes. |

| REFRESH | 7200 | how long secondary nameservers should wait before requesting updates |

| RETRY | 3600 | how long secondary nameservers should wait for asking an unresponsive primary nameserver for an update again |

| EXPIRE | 1209600 | if a secondary nameserver doesn't get a response from the primary nameserver for how long, it should stop responding to DNS queries |

| TTL | 3600 |

# A/AAAA

The 'Address' (A) record stores the actual IP address of the domain. We use A records for IPv4 addresses and AAAA for IPv6 addresses. Here's an example:

example.com. 17460 IN A 93.184.216.34In general, a domain only needs one A record, but occasionally third party services such as Amazon AWS use multiple IPs to achieve load balancing for their hosted services. You can see this with the dig command:

abc.com. 60 IN A 13.226.115.26

abc.com. 60 IN A 13.226.115.14

abc.com. 60 IN A 13.226.115.45

abc.com. 60 IN A 13.226.115.117

abc.com. 300 IN NS ns-1368.awsdns-43.org.

abc.com. 300 IN NS ns-1869.awsdns-41.co.uk.

abc.com. 300 IN NS ns-318.awsdns-39.com.

abc.com. 300 IN NS ns-736.awsdns-28.net.

abc.com. 900 IN SOA ns-318.awsdns-39.com. awsdns-hostmaster.amazon.com. 1 7200 900 1209600 86400# CNAME

Quoting CloudFare's vivid description:

The 'canonical name' (CNAME) record is used in lieu of an A record, when a domain or subdomain is an alias of another domain. All CNAME records must point to a domain, never to an IP address. Imagine a scavenger hunt where each clue points to another clue, and the final clue points to the treasure. A domain with a CNAME record is like a clue that can point you to another clue (another domain with a CNAME record) or to the treasure (a domain with an A record).

When performing a DNS lookup, the DNS will repeat the lookup process on the alias domain specified in the CNAME record until it finds a valid A record (and subsequently the desired IP). Since using a CNAME record effectively deflects control to its alias, the RFC declares that a domain with a CNAME record may not have other common records (such as NS, MX, TXT), with the exception of DNSSEC-relevant records (specifically RRSIG and NSEC).

Hmm, you may wonder, what's the point of having multiple domains pointing to the same alias since they resolve to the same IP? It's the same site anyway, so why do we need aliases?

The logical trap here lies in the misconception that only one site can run on a certain port of a certain machine. In fact, the web server is capable of delivering different websites based on the supplied URL. Say, for example, you have two domains blog.abc.com and news.abc.com both pointing to abc.com with CNAME records. When you type http://blog.abc.com/ in your browser, the server will differentiate via the URL and know you're trying to access the company's blog instead of the news or main site. The pro is ease of maintenance since you can simultaneously configure 3 sites by adjusting records for abc.com.

# NS

The 'Name Server' (NS) record specifies the Authoritative DNS for this domain. As previously mentioned, a DNS zone commonly has a primary nameserver and several secondary nameservers, thus you're highly likely to find multiple NS records for a domain.

$ dig any onedegree.hk

;; ANSWER SECTION:

onedegree.hk. 21600 IN NS ns1-03.azure-dns.com.

onedegree.hk. 21600 IN NS ns2-03.azure-dns.net.

onedegree.hk. 21600 IN NS ns3-03.azure-dns.org.

onedegree.hk. 21600 IN NS ns4-03.azure-dns.info.

onedegree.hk. 3600 IN SOA ns1-03.azure-dns.com. azuredns-hostmaster.microsoft.com. 20200910 3600 300 2419200 300

...Note that a subdomain can also specify its own set of NS records, though for administration purposes we usually set records that represent the entire DNS zone under the base domain (or root of the zone).

# MX

The 'Mail Exchange' (MX) record points to the domain's email-hosting domain, which may be a subdomain or external domain.

For example, at OneDegree we host our email service with Microsoft Outlook:

onedegree.hk. 3600 IN MX 0 onedegree-hk.mail.protection.outlook.com.To send an email to receiver@onedegree.hk, your email server first looks up MX records for onedegree.hk and discover that emails should be sent to onedegree-hk.mail.protection.outlook.com. It then delivers the email via the SMTP protocol to the actual IP of the outlook server. You can't deliver emails without indicating MX records, analogous to how pilots can't fly without knowing the destination airport.

To ease maintenance, you can configure multiple MX records to specify several mail servers, but how does your email server know which record to use when there's no 'primary mail server' specified in the SOA record?

In the example above, you might have noticed another number '0' preceding the target domain. This is what we call the priority number, with the smallest value taking precedence. When two MX records have different priority numbers, the email server will attempt to deliver to the one with a smaller number, and only try the other one if delivery fails. If the two records have the same priority number, one of them is randomly choosed, effectively resulting in email load balancing.

# TXT

The 'Text' (TXT) record stores, as clear as its name, any text that the administrator wants to associate with his domains. It was originally intended for leaving comments, but now it's most popular function is to prevent spam, enforce email authentication protocols, and claim domain ownership.

Technically, any free form text is allowed. Even though the RFC defines a key-value format separated by a single equal and surrounded by quotes, like this: "attribute=value", not all TXT records follow the spec.

To prevent spam and fraud emails, we often enforce three popular email authentication protocols in modern email servers: SPF, DKIM, and DMARC. These methods combined help us achieve email security via IP validation, cryptography, reporting mechanisms, and verification policies. We publish TXT records to communicate and realize these protocols. For a detailed explanation, see my series of articles on email security:

關於 email security 的大小事 — 原理篇

關於 email security 的大小事 — 設定篇 SPF

關於 email security 的大小事 — 設定篇 DKIM、DMARC

關於 email security 的大小事 — 範例篇

關於 email security 的大小事 — 延伸篇

On the other hand, when we want to use third party services, such as sending from our domain with SendGrid or specifying our own subdomain on some ecommerce platform, we often have to prove our ownership of the desired domain, otherwise an attacker might try to register the service and masquerade as our company to trick customers. To accomplish this, we are required to publish a TXT record with specific text to prove that we are indeed in control of the domain. This is analogous to how you have to click on a confirmation email when registering for certain websites.

For instance, websites often configure Google Analytics (GA) to help the marketing people understand user behavior. Since such information usually contains excessive or sensitive business details, Google asks users to prove their rightful authority of the domain during setup to prevented unwarranted access. You will have to publish "google-site-verification=<long-random-string>" in your DNS, and Google will attempt to fetch and verify this TXT record.

Here are some TXT records of onedegree.hk. You can see multiple verification records and a SPF record:

onedegree.hk. 3600 IN TXT "facebook-domain-verification=etkvd5dxxpnlcjkol3e1vi3k348k03"

onedegree.hk. 3600 IN TXT "google-site-verification=kEw0MSSQxwrU4d5GXYBTL6HLTwnQW4aJjh8Om-NTY4Q"

onedegree.hk. 3600 IN TXT "google-site-verification=EntX-1hrFmMHtANmXdTE4rpEwSxpsZGwnVUPWA9476A"

onedegree.hk. 3600 IN TXT "VXZDM75TVG5AVR81FP8ZS1Q3RTRJCPO1LFMCGU6G"

onedegree.hk. 3600 IN TXT "v=spf1 include:spf.protection.outlook.com include:servers.mcsv.net include:email.freshdesk.com -all"# SRV

The 'Server' (SRV) record is relatively less known, and is used primarily to support specific multimedia and messaging protocols such as SIP and XMPP. Details of the SRV record is defined in RFC 2782.

In contrast with other records that usually only specify a domain or IP, the SRV record also indicates the port number and intended protocol. The format is:

_service._proto.name. TTL class type priority weight port target

_xmpp._tcp.example.com. 86400 IN SRV 10 5 5223 server.example.comIt reads: to access the XMPP service via TCP on example.com, find port 5223 on server.example.com.

Now, what are the priority and weight values? Similar to the aforementioned MX records, both parameters are used to distribute load to the destination servers. However, comparison is now two-fold.

Quoting wiki:

Clients should use the SRV records with the lowest-numbered priority value first, and fall back to records of higher value if the connection fails. If a service has multiple SRV records with the same priority value, clients should load balance them in proportion to the values of their weight fields.

Let's illustrate with an example, also taken from wiki:

_sip._tcp.example.com. 86400 IN SRV 10 60 5060 bigbox.example.com.

_sip._tcp.example.com. 86400 IN SRV 10 20 5060 smallbox1.example.com.

_sip._tcp.example.com. 86400 IN SRV 10 20 5060 smallbox2.example.com.

_sip._tcp.example.com. 86400 IN SRV 20 0 5060 backupbox.example.com.The first three records share a priority of 10, so unless all three server fails, the fourth record backupbox.example.com will not be adopted. Furthermore, the first three records have weight of 60, 20, and 20, meaning that 60% of the time bigbox.example.com will receive loading, with the rest equally split between smallbox1.example.com and smallbox2.example.com. Also, if bigbox.example.com is not responding, then smallbox1.example.com and smallbox2.example.com will each have to process 50% of the traffic.

# PTR

The 'Pointer' (PTR) record is effectively the inverse of the A record. Whereas the A record gives a mapping from a domain name to an IP, the PTR record points to the canonical name of an IP and is commonly used for reverse DNS lookups.

Since all records must be stored under a domain name but PTR records represent IPs, we can fill in the gap by constructing a domain name - reversing the IP and adding ".in-addr.arpa" as a suffix. Now the PTR record for 14.13.12.11 will be under the domain "11.12.13.14.in-addr.arpa". In IPv6, the reversed IP is converted into 4-bit sections and prepended before ".ip6.arpa", so 2001:db8::567:89ab becomes b.a.9.8.7.6.5.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.8.b.d.0.1.0.0.2.ip6.arpa.

Why .arpa? ARPA was originally an acronym for 'Advanced Research Projects Agency', the pioneer of the internet, but is now redefined as 'Address and Routing Parameter Area'. The .arpa domain is used by IETF to administer the internet infrastructure, does not provide registration, and rarely adds subdomains.

# Conclusion

As the phonebook of the internet, DNS has been shouldering the massive responsibility of navigating communication across the world. Since the 1980s, the DNS has gone through several revisions and enhancements, but it wasn't originally designed with cybersecurity principles in mind. Thus with the advent of unforeseen technologies and farfetching applications, vulnerabilities began surfacing as various forms of attacks appeared.

In order to discuss attacks on the DNS, we tried giving everyone a brief and basic introduction to the DNS. The next article will bring us to common attack techniques on the DNS and the respective defenses or mitigations against them.

Much of this post is based on Wikipedia and Cloudfare DNS Learning, which offers comprehensive and in-depth knowledge on these topics.

Tag

Recommendation

- Red Team Hero's Certification Adventure Guide

- Practical Applications and Challenges of OpenAI Embeddings and Retrieval-Augmented Generation

- How to Choose a Safe Exchange

- Understanding Log4j and Log4Shell Vulnerabilities from Surveillance Cameras

- The Difference Between Java and Golang in Writing Concurrent Code to Access Shared Variable

Discussion(login required)