When writing concurrency code, we often use mechanisms like Lock or Synchronized to protect share resources (sometimes it’s a piece of code). What if we merely want to protect one variable but not a whole code? It’s too expensive to use Lock or Synchronized to protect just one variable.

Let’s see one simple Golang code:

func BenchmarkLocke(b *testing.B) {

for n := 0; n < b.N; n++ {

a := 0

var l sync.Mutex

for i := 0; i < 10000; i++ {

l.Lock()

a++

l.Unlock()

}

}

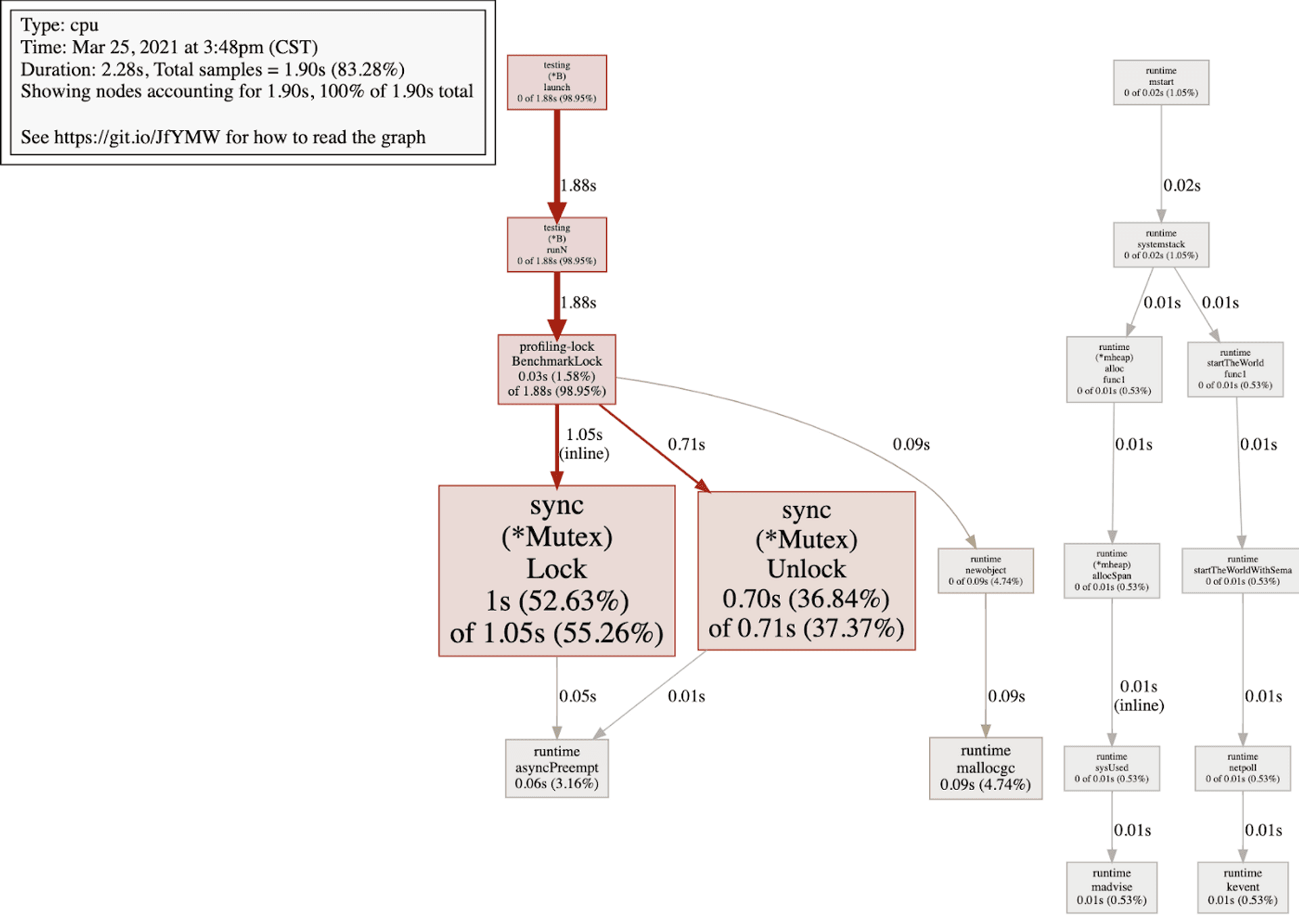

}And profiling of the code will tell you how expensive Lock cost, as shown below:

You can see that lots of CPU time were wasted in Lock.

To improve performance, often we would not use lock if we just want to protect one variable instead of the piece of code.

In this article, I will introduce how to protect these share variables in Java and Golang.

In the very beginning, three things need to care: atomicity, visibility, and ordering. It’s too hard to understand from words, so let’s see examples directly.

# Atomicity

The action to access shared variable must be executed all in once and indivisibly. A line of code may be composed of several cpu instructions, like the codei++ is composed of 3 cpu instructions: read value, add 1 to value and save value. If two threads run i++ simultaneously, all these cpu instructions may be executed interleaved:

thread1 load value 100

thread2 load value 100

thread1 add 1 to value 101

thread2 add 1 to value 101

thread1 save value 101

thread2 save value 101Finally, we get a wrong answer: i = 101, which is not correct.

Let’s look at a simple Java example :

public class Atomic {

public static void main(String []args) throws InterruptedException {

int times = 100000;

ExecutorService executorService = Executors.newFixedThreadPool(1000);

Counter counter = new Counter();

for (int i=0;i<times;i++) {

executorService.execute(new Thread(() -> {

counter.i++;

}));

}

Thread.sleep(20000);

executorService.shutdown();

System.out.println(counter.i);

}

static class Counter {

int i;

}

}Line 16 should print 100000, but the value printed is always less than 100000. That’s why we must care about atomicity.

# Visibility

In Multicore architecture, every CPU has its cache. Thus CPU can load value from cache, which is faster than loading value from main memory. The architecture looks like below:

So it’s clear that the value of a variable may exist in multi CPU’s cache. If cpu1 changes the value of one variable but cpu2 did not aware of that, cpu2 may use the old value until cpu2 reload the value from main memory.

Here is simple Java code to show the problem:

public static void main(String []args) throws InterruptedException {

Flag flag = new Flag();

Thread t1 = new Thread(()->{

while(flag.bool) {

// do nothing

}

});

t1.start();

Thread t2 = new Thread(()->{

flag.bool = false;

});

t2.start();

t1.join();

System.out.println("Unreachable");

}

static class Flag {

boolean bool = true;

}Even thread t2 had changed the flag to true in line 12, thread t1 would still live in an infinite loop in line 4~6. That’s because t1 does not see a new value of the flag.

# Ordering

Sometimes the compile would reordering instructions due to the purpose of optimizations. As a result, the ordering of instructions running in your machine may not as your imagination. See these three codes:

a = 1

b = 2

c = a + bline 3 is a dependency on line1 & line2, so the real ordering of instructions may like below:

b = 2

a = 1

c = a + bIt’s ok when your code is running on a single thread. But when running on multi-thread, the reordering may cause some bug you can not understand. Take the code for example:

private static int a=0,b=0;

public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception {

int i=0;

for (; ;) {

i++;

Thread t1 = new Thread(()->{

a=2;

b=1;

});

t1.start();

if (b==1 && a==0) {

String err = String.format("%th round, Non thread safe!", i);

System.err.println(err);

break;

}

t1.join();

}

}In the writing order, we assign a=2 first and then b=1, so it should never happen that the code runs the block behind the if condition in line 12. But it’s possible. Although it’s very rare to happen, it DO happen.

Note that visibility and ordering are often seen together as the problem of happen-before.

It’s common that implementing singleton pattern with double-checked locking to improve performance. If you were not aware of happen-before, it may cause some issue: even if the singleton instance is not null, that does not mean that system had finished constructed the singleton instance. You can see more detail in this wiki.

So let’s see how Java and Golang solve these issues.

# Java

# How Java solve Atomicity

Java provides package java.util.concurrent.atomic to guarantee the atomicity when accessing a shared variable. For example, we could use AtomicInteger to fix the first example in the beginning like below:

public static void main(String []args) throws InterruptedException {

int times = 100000;

ExecutorService executorService = Executors.newFixedThreadPool(1000);

Counter counter = new Counter();

for (int i=0;i<times;i++) {

executorService.execute(new Thread(() -> {

counter.i.incrementAndGet();

}));

}

Thread.sleep(20000);

executorService.shutdown();

System.out.println(counter.i.get());

}

static class Counter {

AtomicInteger i = new AtomicInteger(0);

}# How Java solve happen-before

Java uses keyword volatile to ensure happen-before. Once you declare a variable with volatile, then happen-before is guaranteed in that variable.

Let’s look at the secondary example in the beginning, I use volatile to declare the variable as below:

public static void main(String []args) throws InterruptedException {

Flag flag = new Flag();

Thread t1 = new Thread(()->{

while(flag.bool) {

// do nothing

}

});

t1.start();

Thread t2 = new Thread(()->{

flag.bool = false;

System.out.println(flag.bool);

});

t2.start();

System.out.println(flag.bool);

t1.join();

System.out.println("Unreachable");

}

static class Flag {

volatile boolean bool = true;

}Now when thread t2 updates bool variable in Flag, thread t1 would be aware of that and escape from the for loop.

Then the third example. After I declare variables a and b with volatile, Compiler would make sure that a=2 happen before b=1, so it would guarantee that the program never enters if statement.

private volatile int a=0,b=0;

public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception {

int i=0;

for (; ;) {

i++;

Thread t1 = new Thread(()->{

a=2;

b=1;

});

t1.start();

if (b==1 && a==0) {

String err = String.format("%th round, Nonthread safe!", i);

System.err.println(err);

break;

}

t1.join();

}

}# Golang

# How Golang solve Atomicity

Golang provides its atomicity tool kit, too.

Do you remember the Golang’s Lock example at the beginning of the article? We can use atomic instead of Lock:

func BenchmarkFib10(b *testing.B) {

for n := 0; n < b.N; n++ {

a := int64(0)

for i := 0; i < 10000; i++ {

atomic.AddInt64(&a, 1)

}

}

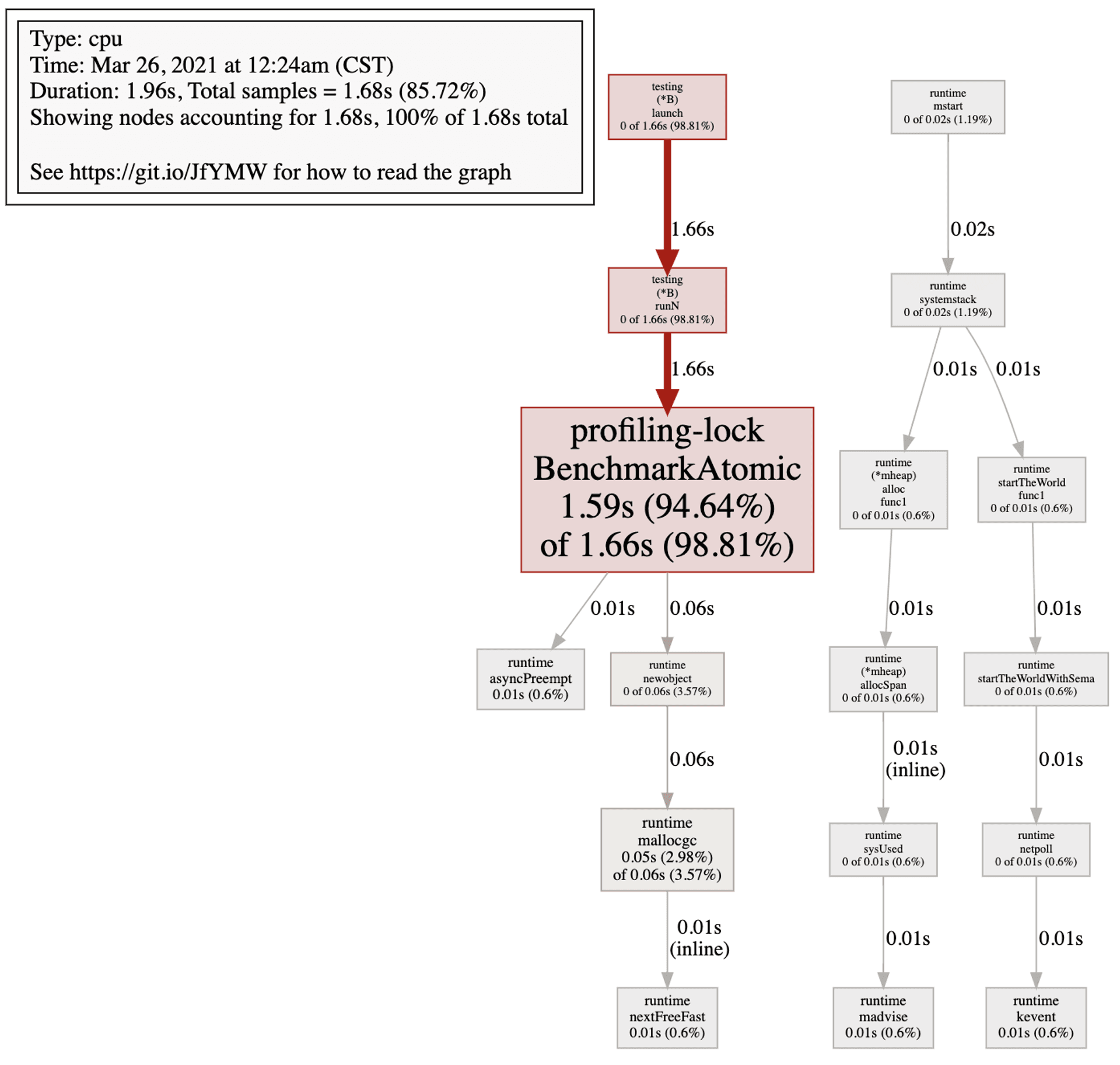

}If you run benchmark, you would figure out the performance gap between Lock and atomicity:

BenchmarkLock-8 9266 134075 ns/op 8 B/op 1 allocs/op

BenchmarkAtomic-8 19225 62309 ns/op 8 B/op 1 allocs/opAnd below is the profiling of atomicity:

# How Golang solve happen-before?

According to Golang’s official blog, Golang would guarantee happen-before in these conditions:

- Initialization

- Goroutine creation

- Goroutine destruction

- Channel communication

- Locks

- Once

But Golang does not provide something like volatile in Java to protect one variable share between goroutines. In terms of visibility, Such as below code may be incorrect synchronization:

func main() {

flag := true

go func() {

for flag {

continue

}

fmt.Printf("Never end\n")

}()

flag = false

for {

continue

}

}line 5~10 would never end.

Then ordering. The Official Goalng Blog mentions that this code is non-concurrence safe:

var a, b int

func f() {

a = 1

b = 2

}

func g() {

print(b)

print(a)

}

func main() {

go f()

g()

}It may happen that g prints 2 and then 1. So we must protect that variable with something like Lock to protect it. But how come an effective Language like Golang would handle this issue in such a heavy way?

Look at this Golang’s official blog, we can see how to solve the issue in Golang way. The blog mentions that:

Do not communicate by sharing memory; instead, share memory by communicating.

That’s the way Golang encourages you to do: using CSP model. So I think the key way to solve the shared variable in concurrency in Golang is “NOT TO SHARE IT”. Instead, you should use chan to communicate. And as mentioned above, chan DO guarantee happen-before!

According to discuss above, I think it should pass flag through chan in the visibility example:

func main() {

done := make(chan bool)

go func(done <-chan bool) {

flag := true

for flag {

select {

case flag = <-done:

break

}

}

fmt.Printf("End of goroutine\n")

}(done)

done <- false

close(done)

for {

continue

}

}Also, I think it should pass a and b through chan in the ordering example, the code may look like:

var a, b int

func f(done <-chan interface{}) (<-chan int, <-chan int) {

chana := make(chan int)

chanb := make(chan int)

go func() {

defer close(chana)

defer close(chanb)

chana <- 1

chanb <- 2

for {

select {

case <-done:

return

}

}

}()

return chana, chanb

}

func g() {

print(b)

print(a)

}

func main() {

done := make(chan interface{})

defer close(done)

chana, chanb := f(done)

a = <-chana

b = <-chanb

g()

}# Conclusion

The most difficult part of writing concurrency code is that most of the bug is not determined, uncertain, and can not reproduce easily, thus it’s had to debug.

That’s why we should dig deeper into detail in how a program langue handle concurrency, understand how your code would run in your machine and prevent you from doing thing wrong.

Tag

Recommendation

Discussion(login required)